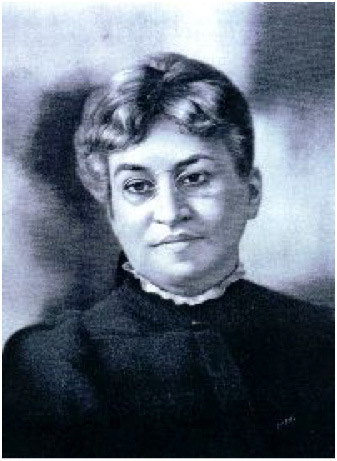

Fannie Richards

Fannie Richards

Detroit’s first Black school teacher, Fannie Richards was born on October 1, 1840 in Fredericksburg, Virginia of free parents. From an early age, Richards realized the necessity of an education and the fight it would take for her to gain it. As a child, she moved to Toronto, Canada with her parents where she received her education.

After permanently settling in Detroit in her early 20s, she began what would become a luminary career as an educator. In 1863, she opened a private school for Black children and in 1868 was appointed instructor of the city's public — but segregated — Colored School No. 2.

Working closely with local politician John Bagley, Richards and several other activists protested against Detroit’s segregated school system, bringing a lawsuit against the Detroit Board of Education on behalf of a Black student who was refused enrollment in his neighborhood public school on the basis of his race. In 1869, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled public school segregation unconstitutional and ordered the Detroit Board of Education to integrate its schools. In 1871, Richards was transferred to the newly integrated Everett Elementary School, where she taught for 44 years. It was there that she established the first kindergarten class in Michigan, inspired by the model's success in Germany in the 1840s.

Richards’ achievements were not limited to education. She helped to found, finance and became president of the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Aged Colored Ladies, an institution organized in Detroit in 1898 to meet the needs of poor and elderly. She was also one of the founders of the Michigan State Association of Colored Women. Richards also taught Sunday School at the historic Second Baptist Church for over 50 years.

In 1915, after more than 50 years of service, she retired from teaching. She died seven years later on February 14, 1922 at the age of 81. She is buried next to her brother, John D. Richards, in Section N, Lot 150.

Richards was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in 1990 for her contributions to education. She was the chief catalyst for the desegregation of Detroit’s schools, 90 years before the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education. A Michigan Historical Marker recognizes her homesite in Detroit.